In 2023, Let’s Rediscover the Natural World through Curiosity

written by Abigail Kingston

In a world suffering from the effects of colonization, profit-driven destruction of natural environments, and industrialization, humans are becoming more and more alienated from the natural world.

When you think of “nature,” what do you envision?

Read more “In 2023, Let’s Rediscover the Natural World through Curiosity”

July 2022 Recent Additions to the Known Biodiversity of the Berea College Forest

July 2022

Five-Banded Thynnid Wasp

Spotted feeding on the nectar of Rattlesnake master flowers. This species seems to be fairly uncommon in KY but it is probably just underreported.

Clubbed Mydas Fly

This is one of the largest flies in KY with wingspans of over 2 inches. This species mimics wasps so it has very few predators. This one was spotted by Berea College student Edie Jo Wakin.

Bog Lygropia Moth

Another new species added by Edie Jo Wakin. This moth was photographed during National Moth Week. As the name suggests this species lives in boggy wet areas.

Eastern Amberwing

Another species first added by Edie Jo, this dragonfly is a great example of a relatively common species that just doesn’t get reported often due to its small size and difficulty to photograph without a telephoto lens.

Dark Phalaenostola Moth

It may not be the prettiest moth out there but it has its charm. The larval host plant of this species is still unknown.

Juriniopsis adusta

This is a species of tachinid fly that parasitizes butterfly and moth caterpillars. This one in particular focuses on tiger moths and skipper butterflies.

Poison Ivy Leaf-miner Moth

Many of the Leaf-miners can be identified by the “tracks” that the caterpillars leave behind while feeding inside of leaves. As you might imagine these are very tiny moths.

Hidalgo Mason Wasp

Found feeding on the nectar of Rattlesnake Master flowers. This species builds its nest in dirt banks and sometimes in the nests of other wasp species.

Fiery Skipper

This is a common species but it hasn’t been documented until this month. Most likely overlooked due to its similarity to other skipper species.

Tulip-tree Silkmoth

Photographed by Kayla Zagray during one of our creepy critter night hikes. This one had a bad wing but it could still fly okay.

Lanceleaf Frogfruit

This species has been found in the Berea College Forest before however, it made its “iNat debut” this month thanks to Kayla Zagray snapping a photo and uploading it to iNaturalist.

Funereal Duskywing

Not only is this species a first for the project it’s also one of the first observations of this species in the state! This species normally lives around Texas and Mexico but vagrants end up in the eastern US from time to time. This one was nectaring in our pollinator garden.

Efferia aestuans

This new species of Robber Fly was found hanging out on the side of the building.

Delta Flower Scarab

This beetle gets its common name from the triangle on the thorax that looks like the Greek letter delta.

Sumac Gall Aphid

Female aphids lay an egg on the bottom of a sumac leaf which induces the leaf to form a gall around the egg. The aphid hatches and reproduces asexually while still inside the gall. In late summer winged females leave the gall and establish new colonies in moss.

Secondary Screwworm Fly

The larvae infest existing wounds and can be a threat to livestock. However, they are also important decomposers of carrion so they aren’t all bad.

Prairie Dock

This is another species that was hiding in plain sight, found just a few feet off of a trail.

Showy Emerald

The larvae of this little green moth feed on Sumac and Poison Ivy.

Zethus spinipes

A type of potter wasp that builds cells for their eggs that look like small pots.

Red Shouldered Bug

The species name for this bug is “haematoloma” which is Latin for blood-fringed … I guess red-shouldered is a little less threatening.

Orange-legged Furrow Bee

This species has the interesting habit of being eusocial in areas with warmer climates and at low elevations and being solitary in high elevations and areas with colder climates.

Tall Tick-Trefoil

Another fairly common species that has just been overlooked due to the similarity to other species in the same family.

Dark-veined Longhorn Bee

Found pollinating one of the native sunflowers in the prairie.

Silky Striped Sweat Bee

We haven’t been able to confirm this one down to species for sure just yet. If this is the correct species it would be one of or possibly the first record in KY.

Round-leaved Boneset

Prefers to grow in wet areas, this one was found along the new burn trail.

Delightful Dagger

Another moth species found by Edie Jo during National Moth Week.

Dicerca lurida

The larvae of this beetle feed on Hickory trees so it makes sense that we found it on the fence under the Hickory tree by the entrance to the trails.

Promiscuous Angle

Another Moth Week addition by Edie Jo.

Golden-reined Digger Wasp

The gold highlights on this wasp were stunning in the sunlight. This picture doesn’t show just how shiny this wasp was.

Spotted Thyris Moth

Spotted nectaring on Rattlesnake Master Flowers, the Larvae of this moth feed on Clematis.

Leucospis affinis

This is a species of parasitoid wasp that is a parasite of many bee species… a video of one laying eggs can be found here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xcMcXH0V7Qo

Physocephala sagittaria

It looks a lot like a wasp but it’s actually a fly.

Belvosia borealis

Another member of the Tachinid flies that parasitize caterpillars.

Stizus brevipennis

A large wasp species that I believe is the first confirmed record in Kentucky. The species name brevipennis refers to its short wings.

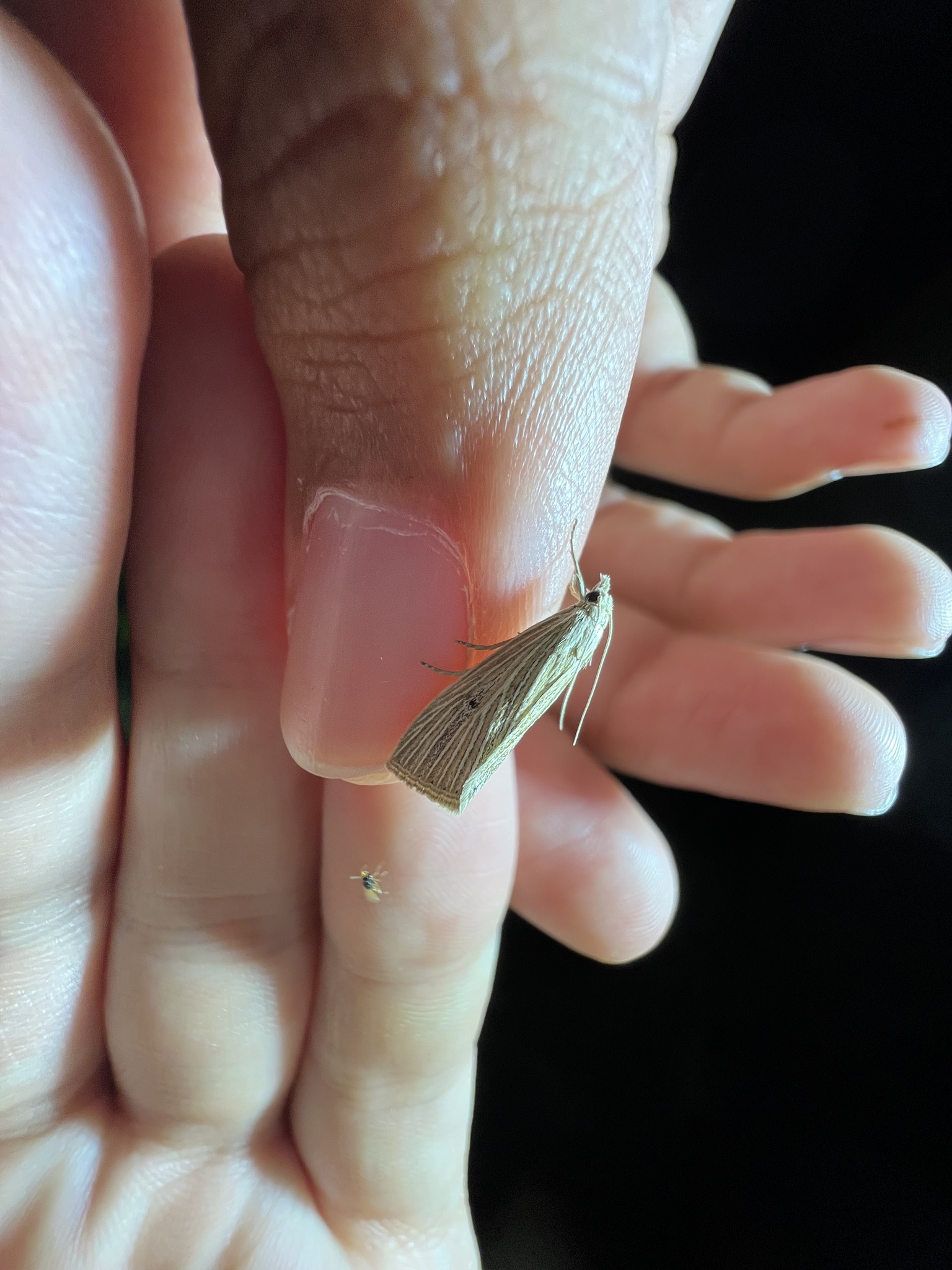

Wainscot Grass-veneer

Small unassuming moth that upon a closer look has a really neat pinstripe pattern.

Can We Predict Eclipses?

by Jeff Hutton

Hello Astronomers! For the last two weeks I’ve shared with you some of the thrill we’ve experienced when we’ve seen eclipses of the Sun and Moon. A solar eclipse happens when the Moon passes in front of the Sun. Lunar eclipses happen when the Moon passes into the shadow of the earth. When do these things happen? Why don’t the happen more often? Want to know? Read on!

Eclipses–Continued

by Jeff Hutton

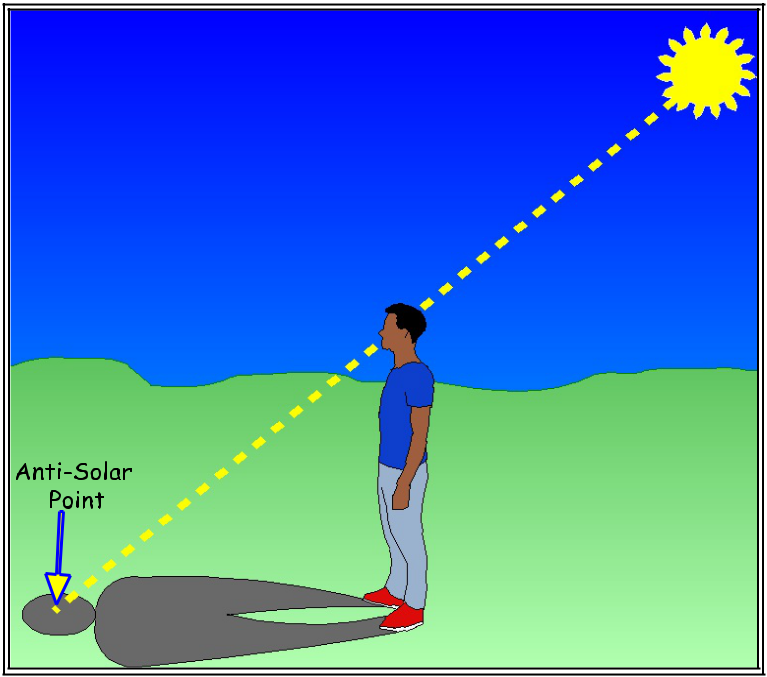

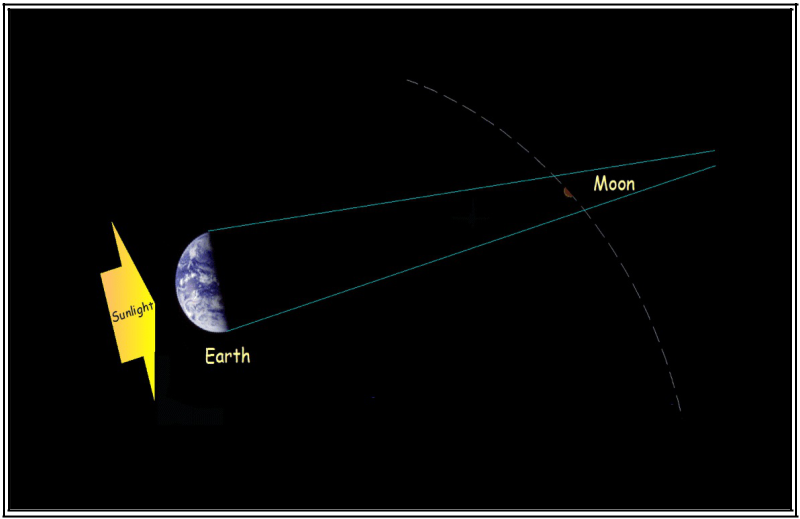

Hello Astronomers! In the last issue, we talked about shadows. Shadows are why we have special events like lunar and solar eclipses. Let’s look again at lunar eclipses. We know that the Earth casts a shadow out into space in the direction of the anti-solar point. Remember, that’s the point directly away from the direction of the sun.

Can we ever see evidence of Earth’s shadow besides when there is an eclipse of the moon? Yes!

Eclipses

by Jeff Hutton

Hello Astronomers! One of the things I love about observing the night sky is that what we see in the sky makes sense, once you apply a little thought to them. For example, think about shadows. You know, light can’t go through solid stuff like your house or your head. Let’s think about shadows.

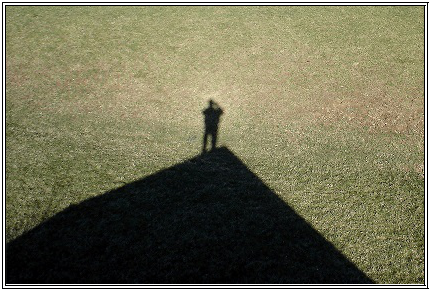

Here’s a picture I took from the roof of my house that shows my shadow. Sunlight is blocked from reaching the ground. The shadow of my head is located at the anti-solar point .

Knowing where the anti-solar point is, helps us to understand a lot about how the Sun affects what we see in the sky. More about that in future articles.

I promised that I would talk to you about eclipses. A solar eclipse happens when the Moon’s orbit carries it to a point in space directly between the Sun and just a small spot on the Earth. The Moon makes a shadow on the Earth just a few miles wide and people like me go to a lot of trouble to get to that spot on Earth just to be in the Moon’s shadow. We love to see scenes just like this!

Here is a picture I took from just the right place and at just the right time in 2017 of the total solar eclipse. We were in Hopkinsville, Kentucky. You’re seeing the night side of the Moon exactly in front of the sun. This view was about as bright as the Full Moon.

This is the ONLY time it is safe to look toward the Sun without special glasses.

The best rule is that you should NEVER look toward the sun. You can cause permanent eye damage or be blinded for the rest of your life. There are special filters and other ways to observe the sun. When we can have in-person talks again at the FOC, I’ll tell you about some of them.

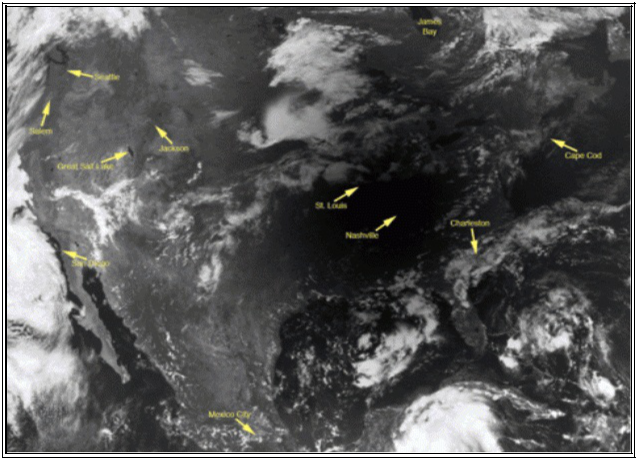

Here’s a picture taken from space at the same time as I took my picture above. Can you make out the shape of North America? The Sun was completely covered-up at the very center of the shadow shown on the Earth. The anti-solar point is at the center of the Moon’s shadow.

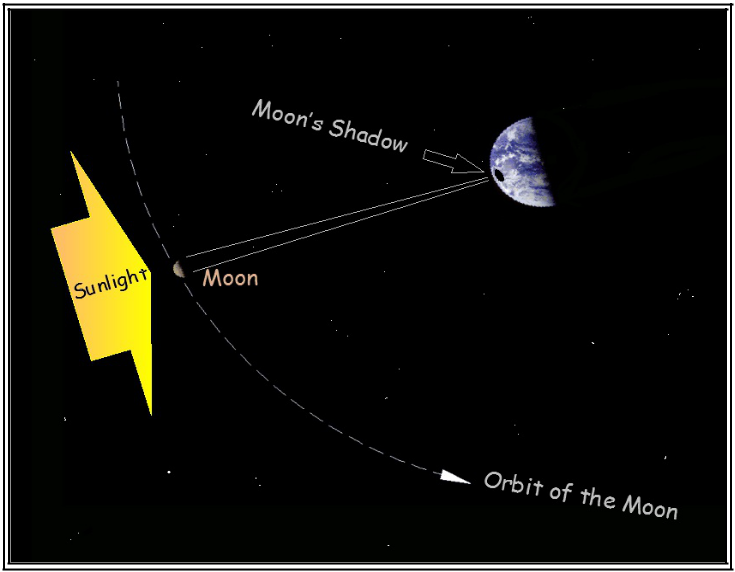

This diagram shows how sunlight on its way to the earth is stopped by the Moon. So the Moon casts a shadow, just like your head, the Moon and the Earth!

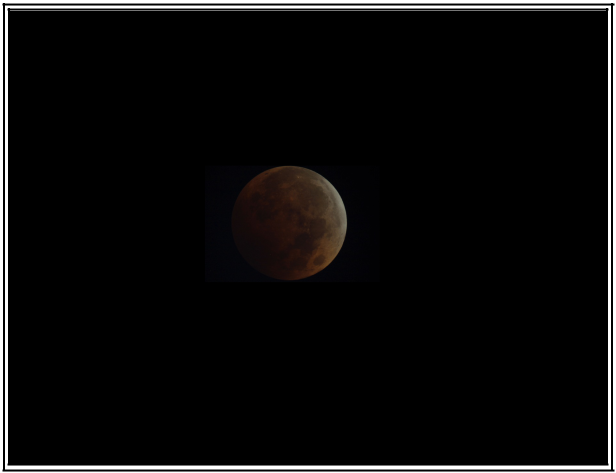

The other kind of eclipse is called a lunar eclipse. I took this picture in 2014. The Earth is much bigger than the Moon. So the shadow that the Moon makes on the earth is pretty small. But the Earth’s shadow is much bigger. It’s so big that the entire Moon can fit inside it! So when this happens, the whole Moon can go dark. The Earth’s the anti-solar point is at the center of its shadow.

Most of the time the Moon looks white and grey but during a lunar eclipse it turns a reddish-orange. That’s because some of the light from the Sun is bent around the Earth by its atmosphere. Did you know that the moon is about as reflective as a piece of black construction paper? Lunar eclipses can turn the Moon almost black or a light orange. More about that later.

could stand on the Moon during a lunar eclipse.

We would near the Earth’s anti-solar point.

Right: This is an real image of the Earth during a solar eclipse, showing the shadow of the Moon as a dark blotch. The anti-solar point is at the center of the shadow.

There’s a lot to know about eclipses. Next time we’ll learn more about when to look for an eclipse and what we can expect to see!

For a printable PDF click HERE.